|

|

|

|

|

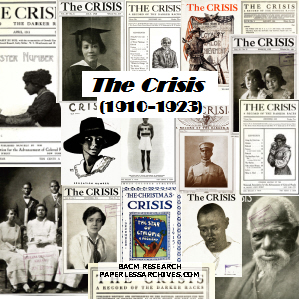

The Crisis - NAACP Magazine (1910 - 1923) |

|

|

|

7,800 pages of The Crisis magazine, every issue published from its first issue, November 1910, through October 1923..

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) established The Crisis magazine in 1910 to provide a magazine for its members. Under the editorship of W.E.B. Du Bois. The Crisis, which Du Bois edited for nearly 25 years, became the premier outlet for black writers and artists.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (1868-1963) was a noted scholar, editor, and African-American activist. Du Bois was a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the largest and oldest civil rights organization in America. A brilliant writer and speaker, Du Bois is considered by many to be the outstanding African-American intellectual of his time. His "The Philadelphia Negro" (1899) was the first sociological study of African-Americans. In The Souls of Black Folk (1903), Du Bois took a forceful stand against Booker T. Washington's policy of accommodation, calling instead for "ceaseless agitation and insistent demand for equality," and the "use of force of every sort: moral persuasion, propaganda, and where possible even physical resistance."

In his first editorial written for the magazine Du Bois wrote, "The object of this publication is to set forth those facts and arguments which show the danger of race prejudice, particularly as manifested today toward colored people. It takes its name from the fact that the editors believe that this is a critical time in the history of the advancement of men. �Finally, its editorial page will stand for the rights of men, irrespective of color or race, for the highest ideals of American democracy, and for reasonable but earnest and persistent attempts to gain these rights and realize these ideals."

The issues included in this "The Crisis" archive includes articles on current events, editorial commentary, essays on culture and history, short stories and poems, reviews, art work, and reports on the achievements of people of color worldwide.

Throughout the years in which Du Bois was the editor of The Crisis, the magazine published the work of many young African-American writers associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Its greatest era as a literary journal was between 1919 and 1926, when Jessie Redmon Fauset was literary editor. Fauset recognized and published the talents of writers such as Arna Bontemps, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Jean Toomer.

The period of time this collection covers coincides with the beginning of an era referred to as the "New Negro Movement." At this time a mass physical movement of African-Americans from the South to the North and West began in the early twentieth century. Later World War I contributed two effects. The increase in industrial activity generated by the war effort caused many northern businesses to recruit African-Americans living in the South to meet labor demands. Outside the South these workers experienced a measurable increase in wages, working and social conditions. Also, approximately 370,000 African-American men served in the armed forces during World War I. After returning home, many of these men sought the freedoms they were told World War I was fought to preserve.

A political shift was occurring among African-Americans, away from the "accommodationist" approach favored by Booker T. Washington, which was giving way to the more "militant" advocacy of W.E.B. Du Bois.

These forces converged to help create the "New Negro Movement" of the 1920s, which promoted a renewed sense of racial pride, economic independence, and progressive politics. Not only politically but culturally and artistically, as shown by the "Negro Renaissance," centered in New York City's Harlem. The Harlem Renaissance, the cultural component of the New Negro Movement, provided the first mass display of African-American cultural self-expression.

The activity of the time is captured in the pages of this collection of The Crisis magazines. Highlights include: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Crisis Volume 1, Number 1, Page 1 - November 1910

Cover of the first issue of The Crisis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Crisis Volume 1, Number 2, Page 26 - December 1910

The first major legal case taken by the NAACP was the defense of Pink Franklin. The NAACP took the case in 1910. Franklin was a black South Carolina sharecropper. When Franklin left his employer after receiving an advance on his wages, a warrant was sworn out for his arrest under an invalid state law. Armed policemen arrived at Franklin's cabin before dawn to serve the warrant without stating their purpose and a gun battle ensued, killing one officer. Franklin was convicted of murder and sentenced to death. The NAACP appealed to South Carolina Governor Martin F. Ansel, and Franklin's sentence was commuted to life in prison. Eventually, he was set free in 1919. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Crisis Volume 6, Number 6, Page 298 - October 1913

In 1912, Democrat Woodrow Wilson received more African-American votes than any other previous Democratic presidential candidate. In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson mandated racial segregation into federal government agencies. African-American employees were separated from other workers in offices, restrooms, and cafeterias. Some blacks were demoted or fired.

Oswald Garrison Villard, a writer for The Nation and NAACP treasurer met privately with President Wilson, recommending that he appoint a National Race Commission to counter the new discriminatory policies. When President Wilson refused, the NAACP released this open letter of protest to the press. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Crisis Volume 10, Number 2, Page 69 - June 1915

When the first exhibitions of the D. W. Griffith film "The Birth of a Nation" look place, the NAACP was alarmed by the content of the film. An idealized portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan as a heroic force. African-American men, played by white actors in blackface, as unintelligent and sexually aggressive toward white women. Birth of a Nation was the first motion picture shown in the White House. Many credit the film as the genesis of the reemergence of the Klu Klux Klan. The NAACP campaign against the film was covered by The Crisis.

The NAACP launched a nationwide campaign to expose the film's distorted history and attempted to halt its showing. The NAACP appealed to censorship boards and government officials to suppress the film. In localities where authorities refused to act against the film, the NAACP picketed the theaters that showed it. The campaign did not stop the film from being seen in record numbers, but in some cities the most offensive scenes were cut and in others the entire film was banned |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Crisis Volume 16, Number 2, Page 76 - June 1918

In April 1918, Congressman Leonidas C. Dyer (R-Missouri) introduced an anti-lynching bill in the House of Representatives, based on a bill drafted by NAACP founder Albert E. Pillsbury in 1901. The Dyer Bill provided for the prosecution of lynchers in federal court. State officials who failed to protect lynching victims or prosecute lynchers could face five years in prison and a $5,000 fine. The victim's heirs could recover up to $10,000 from the county where the crime occurred. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Crisis Volume 17, Number 5, Page 229 - March 1919

The emergence of a period of Ku Klux Klan existence known as the Second KKK (1915�1944) was covered by The Crisis. Soon after The Birth of a Nation was released, a film that mythologized and glorified the first Klan era (1865�1874), new Klaverns starting to form. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NAACP field secretary James Weldon Johnson coined the phrase "Red Summer" to describe the wave of racial violence that exploded across the U.S. during the summer and early fall of 1919. During this time period there were race riots in twenty-five cities, most notably in Chicago, Omaha, Washington, D.C., and Longview, Texas. Johnson went to Washington and reported his investigation of the five-day D.C. riot, which erupted on July 19, when white servicemen began assaulting black pedestrians in response to sensationalized newspaper reports of black men attacking white women. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Crisis Volume 23, Number 5, Page 203 - March 1922

A March 1922 article on Mahatma Gandhi covers the non-cooperation/non-violent theories and practices of the leader of the Indian National Congress.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Crisis Volume 25, Number 3, Page 103 - January 1923

After a prolonged fight, the House of Representatives passed the Dyer Anti-lynching bill on January 26, 1922 by a vote of 230 to 119, but a year of procedure followed by a filibuster by Southern Democrats defeated the bill in the Senate. This prompted a fierce editorial by Du Bois in the January 1923 issue of The Crisis. Du Bois refutes calling the 21 year fight for anti-lynching federal legislation a loss writing, "Many persons, colored and white, are bewailing the 'loss' which Negroes have sustained in the defeat of the Dyer Bill. Rot. We are not the ones who need sympathy. They murder our bodies. We keep our souls. The organization most in need of sympathy, is that century-old attempt at government of, by and for the people, which today stands before the world convicted of failure." |

|

|

|

DOWNLOAD |

|

|

|

Buy now

|

|

|